The funeral flowers had barely wilted when the phone calls began.

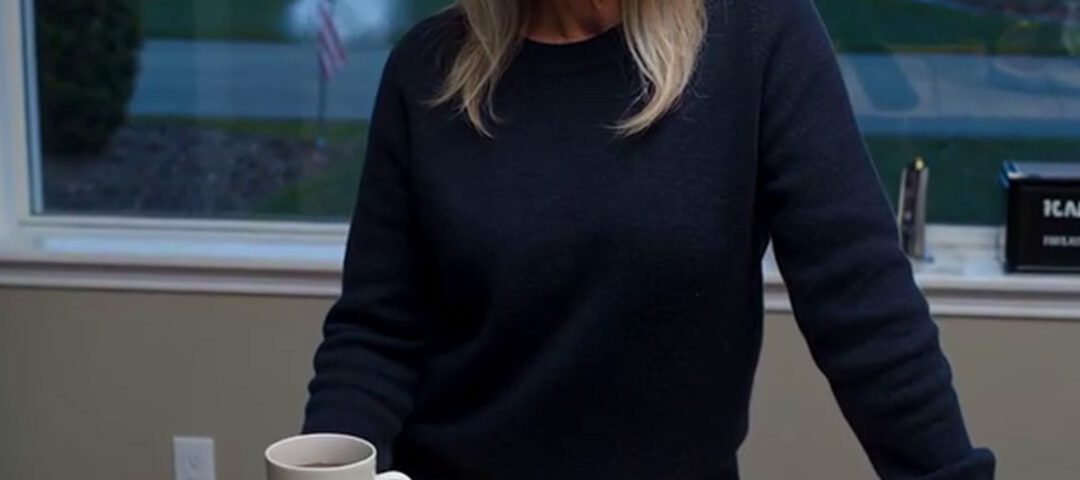

I was standing in my kitchen on a gray Tuesday morning, three weeks after we buried my husband, Russell, watching steam coil off a cup of coffee I couldn’t bring myself to drink. The ceramic mug—white with a faded red heart and the words World’s Best Grandma—had been a Christmas gift from my granddaughter, Kathleen, years ago. It felt foreign in my hands now, the way everything did: the house, my reflection in the hallway mirror, even my own voice when I answered the relentless calls from my children.

“Mom, we need to talk about the house.”

It was my son, Donald. His voice carried that familiar tone of barely contained impatience, the same one he’d used as a teenager when he wanted money for concert tickets or gas. Only now, at thirty-two, he wasn’t asking.

I set the mug down on the kitchen island without taking a sip and looked out through the window over the sink at our quiet Midwestern cul-de-sac. An American flag stirred lazily on the neighbor’s porch, the one Russell used to joke was more punctual than any alarm clock every Fourth of July.

“Good morning to you too, Donald,” I said.

“Don’t start with me, Mom. Lisa and I have been talking about your situation, and frankly, it’s not sustainable. That house is way too big for you alone. The mortgage payments—”

“There is no mortgage,” I said, my voice flat, purely factual.

Russell had paid it off five years earlier, but I’d never mentioned that to the children. They’d assumed, and I’d let them.

There was a pause, then a short laugh—sharp, dismissive, the same sharp edge Russell sometimes had in his voice, though my husband had usually wielded it with affection. Donald wielded it like a weapon.

“Mom, please,” he said. “Dad’s pension barely covers your medications. We all know the financial strain you’re under.”

I walked closer to the window above the sink. The garden Russell and I had tended for twenty-three years was beginning to blur at the edges: roses that needed pruning, an herb patch gone wild where basil and thyme tangled together. These had once been our weekend projects, little rituals of care; now they stood like monuments to everything I’d lost.

“Your concern is touching,” I said, catching my reflection in the glass. Gray hair that needed coloring. Lines around my mouth that had deepened in the past month. Sixty-three years of living etched into features that still surprised me in mirrors.

“Don’t be dramatic,” Donald said. “Darlene agrees with me. We think you should consider moving in with one of us.”

“Darlene agrees,” I repeated, turning away from the window. My daughter hadn’t called me once since the funeral. She hadn’t answered when I’d called her. “And when exactly did Darlene share this opinion?”

Another pause. I could almost see him running a hand through his thinning hair—a gesture he’d picked up from his father.

“We had dinner last night,” he said. “As a family. To discuss your options.”

Your options. Not our mother’s future. Not how we can help Mom through this. My options, as if I were a problem to be solved rather than a person to be supported.

“I see,” I said, opening the refrigerator out of habit, staring at the casserole dishes still stacked inside. Chicken and rice, lasagna, baked ziti. Offerings from well-meaning neighbors, church friends, and Russell’s old coworkers. I hadn’t had the appetite to touch any of them.

“And these options,” I asked, “include selling my home?”

“It makes financial sense,” he said. “You could help Lisa and me with our down payment. We’ve been looking at that colonial on Maple Street—you know, the one near the old elementary school. And Darlene could use some assistance with Kathleen’s college fund. It’s a win-win situation.”

I closed the refrigerator door with more force than necessary.

“A win-win situation,” I repeated.

“Mom, you know I didn’t mean it like that.”

But he had. Donald had always been transparent in his selfishness, even as a child. It was almost refreshing compared to Darlene’s subtle manipulations, the way my daughter had learned to ask for things sideways, making me feel guilty for not offering what she never had to ask for outright.

“What did you tell your sister about my finances?” I asked.

“Just the truth,” he said. “That Dad’s pension isn’t enough. That the house is too big for you to handle alone. That you’re probably struggling more than you’re letting on.”

The truth. As if he knew anything about my actual circumstances. As if any of them had bothered to ask about Russell’s pension in detail, the investments he’d made quietly over the years, or the modest inheritance from his mother that we’d saved and reinvested instead of spending.

I thought about the folder in Russell’s desk drawer, the one I’d found while sorting through his papers after the funeral. Bank statements. Investment portfolios. The deed to a small villa in Marbella that he’d purchased as a surprise for our retirement—a whitewashed house on a street called Calle de las Flores.

“A place where we can watch sunsets and drink wine without anyone asking us for anything,” he’d said, showing me photos on his tablet just six months before his heart attack. The pictures had looked like they belonged in a travel magazine, not in the life of a couple from a quiet American suburb.

“I’ll think about it,” I said finally.

“Mom, we’re not asking you to think about it,” he replied. “We’re telling you what needs to happen. Lisa’s cousin Gregory is in real estate. He already has a buyer looking for something exactly like your place. Cash offer. Quick closing. We could get this done in a month. Start packing your bags.”

My hand tightened on the phone.

“You found a buyer for my house,” I said slowly.

“We’re trying to help you, Mom,” he insisted. “The sooner you accept that this is the best solution for everyone, the easier this transition will be.”

Transition. As if grief were a corporate restructuring. As if dismantling thirty years of marriage and family memories could be reduced to paperwork and profit margins.

“And where exactly am I supposed to live during this ‘transition’?” I asked.

“Well, that’s what we wanted to discuss. Darlene’s got that finished basement, remember? With Kathleen away at college most of the year, there’s plenty of space. You’d have your own entrance, your own bathroom. It could work out perfectly.”

Darlene’s basement. The same basement that flooded every spring. The one where she stored Christmas decorations and exercise equipment she never used. The same basement where I’d been relegated during last year’s Thanksgiving dinner while the “real adults” ate at the dining room table upstairs.

“How generous of Darlene to offer,” I said.

“She’s excited about it, actually,” Donald said. “She thinks it could be good for both of you. You could help with Kathleen when she’s home, maybe do some cooking. You know how Darlene struggles with meal planning.”

Of course I knew. Darlene “struggled” with meal planning the same way she struggled with laundry, cleaning, and remembering to call her mother. She excelled at delegating those struggles to others—especially to the woman who had raised her to be self-sufficient.

“And Donald,” I asked, “what role do you play in this arrangement?”

“Lisa and I will handle the house sale, obviously. The paperwork, the negotiations. We’ll make sure you get a fair price.”

“Fair,” I said. I almost laughed. Donald’s definition of fairness had always tilted in his favor, like a rigged carnival game designed to separate fools from their money.

“I need to think about this,” I repeated.

“Mom, there’s nothing to think about,” he said. “Gregory’s client is serious. They want to close within the month.”

A month. They were giving me thirty days to dismantle the life Russell and I had built. Thirty days to surrender the home where we’d hosted their birthday parties and graduation celebrations, where we’d nursed them through chickenpox and heartbreak and the smaller crises of young adulthood. Thirty days to erase the house with the two-car garage and the American flag on the porch that our neighbors associated with our family.

“I said,” I repeated quietly, “I need to think about it.”

“Fine,” he said. “But don’t take too long. Good opportunities don’t wait around forever.”

The line went dead.

I stood in my kitchen, holding the phone, listening to a silence that suddenly seemed to echo through the entire house. Outside, a neighbor’s dog barked down the street. A car door slammed. Somewhere a delivery truck rumbled past. Life went on as usual in our neat little American subdivision, while mine felt like it was spinning out of control.

I walked down the familiar hallway to Russell’s study, to the oak desk where he’d paid bills and planned our future for more than two decades. The folder was still there, tucked beneath old tax returns and insurance policies.

I pulled it out and spread its contents across the desk’s polished surface. Bank statements showing balances that would make my children’s eyes widen. Investment portfolios that had weathered market storms and quietly grown. The deed to the villa in Spain, with glossy photos of whitewashed walls, blue shutters, and a small terrace overlooking the Mediterranean.

Russell had been a quiet man, methodical in his planning. He’d never boasted about money, never flaunted what we had.

“Let them think we’re struggling,” he’d said once when Donald came asking for yet another “loan” for some new business venture. “It builds character.”

I’d thought he was being cruel. Now I understood it as wisdom.

My phone buzzed on the desk. A text from Darlene.

Mom, Donald told me about the house. I know this is hard, but it’s really for the best. Kathleen is so excited about having Grandma closer. Can’t wait to discuss the details. Love you.

Kathleen. My granddaughter who had spent summers in this house, who had learned to bake chocolate chip cookies in this kitchen and to plant tomatoes in this very garden. The girl who called me every week during her first semester of college, homesick and overwhelmed, seeking comfort from the grandmother who always had time to listen.

When was the last time she’d called?

Two months ago? Three?

I scrolled through my messages, looking for recent texts or missed calls from her. Nothing since Christmas—just a group text thanking everyone for gifts.

No personal messages. No late-night calls about classes or roommates or boys. No questions about how I was coping without Russell.

The silence stretched around me, heavy with realization. They’d already moved on. All of them. Russell’s death had been an inconvenience to be managed, not a loss to be mourned together. And I… I was simply another inconvenience. Another problem requiring their efficient solution.

I closed the folder and slid it back into the drawer, but this time I knew exactly where it was. Then I walked upstairs to our bedroom, to the closet where Russell’s shirts still hung in a tidy row, smelling faintly of the aftershave he liked. I pulled a suitcase down from the top shelf.

It was time to start packing—but not the kind of packing Donald imagined.

The law office smelled of leather and old paper, like Russell’s study distilled and multiplied. On the wall behind the receptionist’s desk hung a framed print of the Manhattan skyline at dusk, all glass and steel and twilight, a reminder that even in a quiet Ohio town like ours, people still dreamed in big-city images.

I sat across from Connie West, the estate attorney Russell had chosen years ago. She was in her fifties, sharp-featured with silver-streaked hair and eyes that missed nothing.

“Mrs. Lawson,” she said, spreading several documents across the gleaming mahogany desk. “I have to say, this is highly unusual. Your husband was very specific about these contingencies, but I never expected we’d need to implement them.”

I smoothed the black dress I’d worn to Russell’s funeral—the only “formal” black dress I owned—and kept my voice steady.

“Russell always said I underestimated people’s capacity for selfishness,” I replied. “I’m beginning to think he was protecting me from a truth I wasn’t ready to see.”

Connie nodded. Her fingers traced the edge of a document stamped with the bank logo.

“The revocable trust he established gives you complete control over all assets,” she explained. “Your children were never named as beneficiaries of the real estate. Only of the life insurance policy. Everything else—the house, the investments, the property in Spain—belongs entirely to you.”

“And they don’t know about the property in Spain,” I said.

“According to your husband’s instructions, that information was to be shared only with you and only after the initial thirty-day period following his death,” Connie said. “He seemed to anticipate that your children might pressure you into hasty decisions immediately after the funeral.”

“Pressure,” I said. “That’s a polite word for what Donald has been trying to do.”

I thought of his voice on the phone, demanding rather than requesting, speaking to me as if I were an incompetent child instead of the woman who had raised him.

“The house sale they’ve arranged,” I asked. “Can it be stopped?”

Connie’s lips twitched into a thin, satisfied smile.

“You’re the sole owner,” she said. “No sale can proceed without your signature. If they’ve already found a buyer and made promises, they’re operating under false assumptions. Russell was very clear about protecting your autonomy.”

Something loosened in my chest, a knot I hadn’t realized I’d been carrying since the day of the funeral.

“And the Spanish property?” I asked.

“Also fully paid for and legally yours,” Connie said. “The property management company your husband contracted with sends monthly reports. The house has been maintained and is ready for occupancy whenever you choose.”

Whenever you choose. When was the last time anyone had spoken to me about choice instead of obligation?

Connie pulled out a cream-colored envelope and set it gently in front of me.

“There’s something else,” she said. “Your husband asked me to give you this letter exactly one month after his death. Today marks that date.”

My hands trembled as I opened the envelope. Russell’s careful, looping script filled the page. As I read, it felt as if his voice was in the room, woven into the sound of the air conditioner and the rustle of paper.

My dearest Michelle,

If you’re reading this, it means I’m gone and you’re dealing with the aftermath alone. I know our children—love them though we do—and I suspect they’re already circling like vultures, convinced they know what’s best for you.

They don’t.

You are not a burden to be managed or a problem to be solved. You are an intelligent, capable woman who raised two children, supported a husband through his career changes, and managed our household with grace for over thirty years. Don’t let them convince you otherwise.

The money and properties are yours to do with as you please. Keep them, sell them, give them away. It’s your choice. But make that choice based on what you want, not what others expect from you.

I’ve watched you sacrifice your own dreams for decades, always putting our family first. Now it’s time to put yourself first. Go to Spain if you want. Travel. Write that novel you always talked about. Do whatever brings you joy. The children will survive without your constant sacrifice. In fact, they might even grow stronger for it.

With all my love and faith in your strength,

Russell

P.S. The key to the Spanish house is in my desk drawer behind the photo of us in Venice. Mrs. Rodríguez next door has been caring for the garden and speaks excellent English.

I read the letter twice, my vision blurring at the edges. Russell had seen what I’d been too close to recognize: that our children had learned to view my love as a resource to be exploited rather than a gift to be cherished.

“Are you all right?” Connie asked gently.

I folded the letter and slid it back into its envelope, cradling it like something fragile and irreplaceable.

“I’m better than I’ve been in weeks,” I said. “What do I need to do to transfer the house deed into my name alone?”

Connie blinked.

“It’s already in your name alone,” she said. “Your husband removed the children from all property deeds three years ago, after Donald asked him to co-sign on that restaurant investment. Do you remember that?”

I did. I remembered the arguments at our kitchen table, Donald’s face flushed with anger when Russell refused to put our retirement savings on the line for his “sure thing.” At the time, I’d thought Russell was being harsh.

Now I saw it as something else: foresight.

“There’s one more thing,” Connie said, pulling out a smaller envelope. Inside was a bank card taped to a folded sheet of paper. “Your husband asked me to give you this as well. It’s connected to an account he opened last year. He called it your ‘independence fund.’”

The weight of the card felt strangely solid in my palm.

“How much is in it?” I asked.

“Fifty thousand dollars,” Connie said. “He deposited money every month, telling me it was for ‘when Michelle finally decides to live for herself.’”

Fifty thousand dollars. Money I’d never known existed. Saved from his pension and investment dividends while I’d carefully budgeted our household expenses, clipping coupons and checking grocery circulars like I always had.

Money not meant to make me feel safe—but free.

I left the law office with a briefcase full of documents and a clarity I hadn’t felt since before Russell’s heart attack. The house was mine. The Spanish villa was mine. The investments were mine. But most importantly, the choice of what to do with all of it was mine alone.

My phone rang just as I reached my car. Darlene’s name flashed across the screen.

“Mom, I’m so glad I caught you,” she said when I picked up. I could hear traffic in the background, the constant hum of life in the suburban strip-mall universe just beyond my quiet street. “I wanted to talk about the basement renovations. Lisa knows a contractor who could put in a kitchenette for you. Maybe a separate entrance. It would be perfect. Your own little apartment.”

I unlocked the car but stayed standing on the asphalt, the late-morning sun warming my back.

“How thoughtful,” I said.

“I know you’re probably worried about the cost,” she continued, “but Donald and I figured we could deduct it from the house sale proceeds. Think of it as an investment in your comfort.”

My comfort. Not my independence. Not my happiness. My comfort, as if I were an elderly pet being relocated to more manageable quarters.

“Darlene,” I said, “when was the last time you called me just to see how I was doing?”

A pause. “What do you mean?”

“I mean a phone call where you didn’t want something,” I said. “Where you asked about my day, my feelings, my plans. When you called because you missed talking to your mother.”

“Mom, that’s not fair,” she said. “I’ve been dealing with Kathleen’s college expenses, and you know how busy work has been.”

“Kathleen’s college expenses,” I repeated. I watched a minivan pull into the lot, a mother shepherding two kids in Little League uniforms toward a chain restaurant. America’s idea of convenience, everywhere you looked.

“Tell me about Kathleen’s expenses,” I said.

“Well, tuition is twenty-eight thousand a year,” Darlene said. “Plus room and board, books, her sorority fees—”

“Darlene,” I interrupted, “I’ve been sending Kathleen five hundred dollars every month since she started college. For two years. That’s twelve thousand dollars.”

Silence.

“Money that was supposed to help with her expenses,” I continued. “Money you never mentioned to Donald when you discussed my supposed financial struggles. Have you told Kathleen that I send that money?”

“She knows you help out,” Darlene said carefully.

“Does she know the amount?” I asked. “Does she know it comes from my pension, not from some college fund Russell left behind?”

“I don’t see why those details matter,” she said.

I closed my eyes, feeling something cold and clear settle in my stomach.

“She doesn’t know, does she?” I said softly. “She thinks her college expenses are covered by your hard work and sacrifice. She has no idea that her grandmother has been quietly funding her education.”

“Mom, you’re making this more complicated than it needs to be,” Darlene said.

“Am I?” I asked. “Or am I finally seeing how simple it actually is?”

I hung up and got into the car. My hands were shaking—but not from grief this time. From anger. Clean, bright anger that felt less like an explosion and more like waking up.

At home, I went straight to Russell’s desk and opened the drawer he’d mentioned in his letter. The key was exactly where he’d said it would be, small and brass, attached to a keychain with a tiny Spanish flag. Behind it was a photograph I’d forgotten existed: Russell and me in Venice on our twenty-fifth anniversary, both of us laughing at something the photographer had said. I looked younger in that photo, but not just because of smoother skin or darker hair. I looked younger because I looked unguarded. Happy.

My phone buzzed again. A text from Donald.

Mom, Gregory needs an answer by tomorrow. His client is getting impatient. Don’t mess this up for all of us.

Don’t mess this up for all of us.

I deleted the message without replying, opened my laptop on the kitchen table, and searched for the property management company’s website. It took me twenty minutes to find the right email address and another ten to compose a message.

Dear Mrs. Rodríguez,

My name is Michelle Lawson, and I am Russell’s widow. I believe you have been caring for our house on Calle de las Flores. I am planning to visit Spain very soon and would like to arrange to stay in the house for an extended period. Please let me know what preparations need to be made.

Thank you for your kindness in maintaining the property during this difficult time.

Sincerely,

Michelle Lawson

I hit send before I could talk myself out of it. Then I went upstairs and pulled the suitcase from my closet out onto the bed.

Before I packed anything for myself, I opened the closet in Donald’s old room and began filling boxes with his childhood trophies, his school papers, the baseball glove Russell had bought him for his tenth birthday. Everything that mattered from his time in this house, carefully wrapped and labeled.

I was halfway through packing up Darlene’s old room—her cheerleading medals, piano books, the framed photo from her high school graduation—when my phone rang again. An international number.

“Mrs. Lawson, this is Pilar Rodríguez,” a woman’s warm voice said when I answered. “I just received your email, and I am so sorry for your loss. Russell spoke of you often.”

Her English was accented but clear, each word wrapped in a kindness that made my throat tighten.

“Thank you, Mrs. Rodríguez,” I said. “I hope it’s not too much trouble, but I’m thinking about coming to Spain quite soon.”

“Oh, no trouble at all,” she said quickly. “The house is ready. I check on it every week, and the garden is beautiful. Russell would be so happy to know you were coming. When were you thinking to arrive?”

I looked around Darlene’s childhood bedroom, at the open boxes of memories I was packing for children who now saw me as an obstacle to their inheritance.

“Next week,” I said. “I’d like to come next week.”

The moving truck arrived at seven in the morning, just as Donald’s car pulled into my driveway. I watched from my bedroom window as my son climbed out, his face already arranged in that expression of barely controlled irritation I’d learned to recognize—and dread—years ago.

He was wearing his serious business suit, a pale yellow tie Lisa had picked out for his big interviews, and carrying a thick manila folder that I was sure contained house-sale documents and pre-printed signatures lines.

Perfect timing.

The movers were efficient, broad-shouldered men in navy T-shirts with the company’s name printed across the front, the kind of crew that spends its weekends shifting other people’s lives from one place to another all over our town. I’d hired them to collect the carefully packed boxes from Donald’s and Darlene’s old rooms, along with several pieces of furniture they’d both mentioned wanting “someday”: Russell’s leather armchair, the antique dining set I’d inherited from my mother, the upright piano Darlene had begged for as a child and then abandoned after six months of lessons.

“Ma’am, where do you want these boxes delivered?” the lead mover asked, glancing at his clipboard.

“The first set goes to 247 Maple Street,” I said, handing him Donald’s address in my careful handwriting. “The second set to 892 Pine Avenue. Ring the doorbell and tell them these are gifts from Michelle Lawson. Memories they’ll want to keep safe.”

He nodded professionally, but I caught the faint twitch of a smile at the corner of his mouth. Twenty years in the moving business had probably shown him more family drama than any therapist.

Donald’s sharp knock on the front door interrupted my instructions.

I opened it wearing the red dress Russell had always said brought out my eyes, my hair freshly styled from a little suburban salon down by the Target, looking nothing like the grieving, fragile widow my son expected to strong-arm.

“Mom, what the hell is going on?” Donald demanded, stepping inside. “Why is there a moving truck in your driveway?”

“Good morning, Donald,” I said calmly. “I’m having some things moved.”

He pushed past me into the foyer, his gaze darting to the stacks of boxes near the stairs, each clearly labeled with his or Darlene’s name.

“These are my things,” he said. “My childhood things. Why are you packing up my stuff?”

“I thought you’d want them,” I said. “Memories are precious, don’t you think?”

Color climbed from his collar up his neck, the same mottled red he used to get when he was caught in a lie as a teenager.

“Mom, we need to talk,” he said. “Gregory’s client is ready to make an offer. We need your signature today.”

I closed the door and leaned back against it, watching him pace my entryway like a caged animal. Family photos looked down at us from the walls—school pictures, Christmas mornings, Disney trips I’d scrimped and saved for.

“Donald, sit down,” I said.

“I don’t want to sit down,” he snapped. “I want to know why you’re acting so strange. First, you don’t return my calls for three days, and now there’s a moving truck—”

“Sit down,” I repeated.

Something in my voice stopped him. He sat on the bottom stair, the manila folder clutched in both hands.

“Where exactly did you tell Gregory’s client the money from this house sale would go?” I asked.

“What do you mean?” he said cautiously.

“I mean,” I said, “did you tell them the proceeds would be split between you and Darlene? Did you calculate how much you’d each receive after paying off this mysterious mortgage you’re so worried about?”

“Mom, you’re not thinking clearly,” he said. “Grief can cloud judgment.”

“My judgment is perfectly clear,” I replied. “Clearer than it’s been in years.”

I walked into the living room and sat in Russell’s chair—the same chair the movers would soon carry into Donald’s house, whether he wanted it or not.

“Let me ask you something else,” I said. “When you had that dinner with Darlene to discuss ‘my situation,’ did either of you ask how I was handling Russell’s death emotionally?”

“Of course we care about—”

“Did you ask if I was sleeping?” I pressed. “If I was eating? Whether I needed someone to talk to? Whether I wanted company? Did you ask what I might want to do with my life now that I’m alone for the first time in thirty years?”

He stared at me silently, the folder crinkling under his tightening grip.

“Or,” I asked softly, “did you spend the entire dinner calculating how much money you could extract from your father’s death?”

“That’s not fair,” he muttered.

“Isn’t it?” I reached for my phone and opened the calculator app. “Let’s see. If you sold this house for the amount Gregory mentioned—three hundred fifty thousand dollars—and split it between you and Darlene after imaginary closing costs, you’d each walk away with, what… about a hundred sixty thousand?”

The color drained from his face.

“That’s what I thought,” I said. “Donald, do you know what your father’s pension actually pays me each month?”

“I don’t see why—”

“Four thousand two hundred dollars,” I said calmly. “Every month. Plus his Social Security. Plus dividend payments from investments you know nothing about. Tell me again how I can’t afford to keep this house.”

Donald lurched to his feet, the folder falling to the floor.

“You lied to us,” he said.

“I never lied,” I replied. “You assumed. I didn’t correct your assumptions. There’s a difference.”

“You let us think you were struggling,” he said. “You wanted us to feel guilty.”

“You wanted to think I was struggling,” I said. “It made it easier to justify treating me like a problem to be solved rather than a person to be supported.”

The moving truck’s engine rumbled outside. Through the front window, I watched the men lift Russell’s chair onto the ramp.

“Mom, if you don’t need the money,” Donald said slowly, “then why…?” His brows pulled together, the gears of his businessman’s brain finally catching up. “You’re punishing us.”

“I’m giving you exactly what you asked for,” I said.

“That’s not what we asked for,” he protested.

“Isn’t it?” I asked. “You asked me to move out of my house. I’m moving. You wanted my belongings distributed so they wouldn’t be a burden later. I’m distributing them. You wanted to handle my affairs for me—but the problem, Donald, is that these aren’t your affairs to handle.”

He took a step toward me, hand outstretched as if he could grab the situation and wrestle it back into his control.

“Mom, be reasonable,” he said. “We can work this out. Maybe you don’t have to move into Darlene’s basement. We could find you a nice apartment. Something more manageable.”

“More manageable for whom?” I asked.

The question hung between us like a blade.

My phone rang. Darlene’s name flashed on the screen.

“Answer it,” I told Donald. “Put it on speaker.”

He shook his head, but I picked up and tapped the speaker icon.

“Mom, what is this insanity?” Darlene’s voice crackled through. “There’s a moving truck at my house and two men are trying to deliver a piano I don’t have room for.”

“Hello, Darlene,” I said. “The piano you begged for when you were eight. I thought you’d want it back.”

“I don’t want it back,” she snapped. “I have no room for a piano. And Donald just called me about some crazy idea that you’re not selling the house.”

“The house isn’t being sold,” I said.

Silence.

“What do you mean it’s not being sold?” she demanded.

“I mean exactly what I said,” I replied. “This is my house. Russell left it to me. I’m not selling it.”

“But Donald said you couldn’t afford—”

“Donald was wrong about many things,” I said.

Another silence. Longer this time.

“Mom, I don’t know what game you think you’re playing,” she said at last, “but people are counting on this sale. I’ve already talked to Kathleen about her having a bedroom here when you move in.”

“Speaking of Kathleen,” I said, looking directly at Donald, “when was the last time she called me?”

“I don’t keep track of Kathleen’s phone calls,” Darlene said.

“The last time she called me was December fifteenth,” I said. “Right before Christmas break. She wanted to know if I’d send her money for a spring break trip. She didn’t ask how I was doing. She didn’t mention missing her grandfather. She needed money.”

“Mom, college students are self-absorbed,” Darlene said. “That’s just how they are at that age.”

“Is she self-absorbed,” I asked, “or has she learned from watching her mother that grandmothers exist to provide financial support without expecting emotional connection in return?”

“That’s not—”

“I’m twisting everything?” I asked quietly. “Darlene, how much money have I sent Kathleen over the past two years?”

No answer.

“Twelve thousand dollars,” I said. “Five hundred a month, directly into her account. Money you never mentioned to Donald when you claimed I was financially struggling. Money Kathleen apparently believes comes from your sacrifice, not mine.”

Donald stared at me, his mouth slightly open.

“You’ve been sending Kathleen money every month?” he asked.

“Because I love my granddaughter and want her to succeed,” I said. “But love isn’t supposed to be invisible. Support isn’t supposed to be secret. When did my family decide that my contributions only mattered when they were hidden?”

“Mom, we never meant—” Darlene began.

“Yes, you did,” I said. “You meant exactly this. You wanted my resources without my presence. My money without my opinions. My compliance without my autonomy.”

I ended the call and looked at my son.

“The moving truck will be at your house in thirty minutes,” I said. “I suggest you make room for your childhood memories.”

“Mom, please,” Donald said. “We can fix this.”

“How?” I asked.

He opened his mouth, then closed it again. I waited, but no words came.

“We could have dinner as a family,” he said finally. “Talk about what you really want.”

“What I really want,” I said, surprising myself with a laugh that felt like a crack in an old wall, “is to live the rest of my life surrounded by people who see me as more than a source of emergency funding. I want to wake up in the morning without wondering which of my children will call with their hands out. I want to be missed for my company, not mourned for my money.”

The moving truck’s engine roared to life. Through the window, I watched the last piece of furniture disappear into its cavernous interior.

“Where are you going to go?” Donald asked, voice suddenly small.

“Somewhere warm,” I said, smiling—the first genuine smile I’d felt in months.

He bent to scoop up the fallen papers, his movements hurried, desperate.

“Mom, you can’t just disappear,” he said. “We’re your family.”

“Are you?” I asked softly.

For a moment, I saw not the man with the briefcase and the panicked eyes, but the little boy who used to climb into my lap after nightmares, who needed Band-Aids for scraped knees and stories to chase away the dark.

Then the moment passed.

“When will you be back?” he asked.

I opened the front door, letting in the clean morning light and the sound of the truck pulling away.

“I’ll let you know,” I said.

The flight to Madrid from New York was thirteen hours of crystalline clarity. I sat in the window seat Russell had always preferred, watching the Atlantic spread beneath us like an endless, shifting sheet of steel-blue. The woman beside me—a chatty retiree from Phoenix on her way to visit her daughter stationed at a U.S. base near Rota—tried to make small talk during takeoff, but something in my expression must have warned her off. I wasn’t ready for casual intimacy, for the exchange of life stories with a stranger at thirty thousand feet.

I was too busy savoring the silence of my phone.

For three days after Donald left my house, they had called incessantly—Donald, then Darlene, even Lisa, who had never called me on her own in the five years she’d been married into the family. The voicemails had started apologetic and edged slowly toward frantic.

“Mom, I think we had a misunderstanding.”

“Michelle, it’s Lisa. Donald is really upset. I think if we could just sit down and talk—”

“Mom, Kathleen is asking questions about the money, and I don’t know what to tell her.”

“Fine, Mom. You want to play games? Two can play that game. Don’t expect us to come running when you realize how lonely you are.”

That last message from Darlene had crystallized something for me. The threat was supposed to hurt, to scare me back into compliance. Instead, it felt like a key turning quietly in a lock.

The night I heard it, I’d turned off my phone and slipped it into my purse. I hadn’t turned it back on since.

The customs officer in Madrid was a young woman with kind eyes and a neat bun under her dark-blue cap. She stamped my passport quickly.

“Purpose of your visit, señora?” she asked in accented English.

“Starting over,” I said before I could stop myself.

She smiled, glancing up.

“Welcome to Spain,” she said.

Pilar was waiting for me in the arrivals area, holding a small cardboard sign that said Mrs. Lawson in careful block letters. She was in her early sixties, compact and strong, her silver hair pulled back into an elegant bun. Her eyes crinkled at the corners when she smiled.

“Mrs. Lawson, welcome, welcome,” she said, stepping forward to hug me like an old friend. I startled, then hugged her back.

“How was your flight? Are you tired? Hungry? The house is ready for you. I made some simple food, just basics until you can shop for yourself.”

Her English had that musical Andalusian lilt Russell had imitated when he told me stories about his trips for work years ago.

As we walked to her small Renault in the parking garage, she chattered about the weather, the neighborhood, the garden she’d tended in my absence.

“Russell was so proud of this house,” she said as we drove along the coastal highway toward Marbella, the Mediterranean flashing silver to our right. “He would show me pictures on his phone. You in the kitchen in America, your grandchildren, always your grandchildren. ‘My Michelle will love the kitchen here,’ he said. ‘She will make it sing with life.’”

I pressed my lips together, not trusting my voice. Russell had talked about me here, in this place I’d never seen, to this woman I’d never met. He’d imagined a future for us that his heart never lived long enough to see.

The house took my breath away.

It was smaller than the one we’d had in Ohio, but perfectly proportioned—whitewashed walls, blue shutters, and bougainvillea spilling in purple cascades over the garden walls. Lemon trees, their fruit bright yellow against glossy green leaves, lined the stone path to the front door. Somewhere down the hill, hidden from view, I could hear the sea.

“It’s beautiful,” I whispered.

“Russell chose well,” Pilar said, handing me the brass key from my desk drawer. “Come, let me show you.”

Inside, the air was cool and faintly scented with citrus. Terracotta tiles cooled my feet through my sneakers. The living room had a cream-colored sofa, a wooden coffee table, and built-in bookcases waiting to be filled. Through glass doors, I could see a small terrace with a metal table and two chairs, overlooking a strip of sparkling blue water.

In the kitchen, copper pots hung from hooks above tiled countertops in shades of blue and white that echoed the sea beyond.

“I stocked the refrigerator with basics,” Pilar said, opening cabinets to show me plates, glasses, olive oil, and wine. “There is bread, cheese, fruit. Tonight you rest. Tomorrow we explore the village together, sí?”

“Yes,” I said, nodding, overwhelmed by the kindness of this stranger who owed me nothing and yet had cared for my husband’s dream as if it were her own.

“No thanks necessary,” she said when I tried. “We are neighbors now. In Spain, neighbors are family.” She pointed out the window to a similar house a short walk away. “I live just there. If you need anything, anything at all, you call me. Russell made me promise to take care of you.”

After she left, I stood in the center of the little Spanish kitchen and felt something I hadn’t experienced in months.

Peace.

I unpacked slowly, hanging my clothes in the bedroom closet, placing Russell’s photo from Venice on the bedside table, arranging my toiletries in the bright bathroom with its claw-foot tub and window facing the sea. Each small act felt deliberate, chosen by me, not dictated by someone else’s timeline.

As the sun began to set, I poured myself a glass of the wine Pilar had left and stepped out onto the terrace. The Mediterranean stretched before me, turning gold and rose under the dying light. A few small sailboats bobbed in the distance like white commas on a sentence of blue; the waves met the rocks below with a steady, soothing rhythm.

My phone, forgotten at the bottom of my purse, began to ring. I almost ignored it. I’d successfully avoided all contact for four days.

But the name on the screen made me pause.

Kathleen.

I answered on the fourth ring.

“Grandma, oh my God, finally,” she burst out. “I’ve been trying to reach you for days.”

Her voice sounded different. Not the casual, breezy entitlement I’d grown used to—the “hey, Grandma, can you…?” tone—but something sharper, more focused.

“Hello, Kathleen,” I said, sitting down in one of the terrace chairs.

“Where are you?” she demanded. “Mom won’t tell me anything except that you had some kind of fight with her and Uncle Donald and now you’re ‘gone’ and there’s all this weird drama about a house sale that didn’t happen.”

“Kathleen, slow down,” I said.

“I can’t slow down,” she said. “I’m furious. Do you know what I found out? Do you know what Mom told me yesterday?”

I watched the last slice of sun slip into the sea.

“What did she tell you?” I asked.

“She told me you’ve been sending me money for college,” Kathleen said. “Five hundred dollars every month for two years. She said it like it was this big burden she’d been hiding from me to ‘protect’ me. But Grandma—”

Her voice cracked.

“Why didn’t you tell me?” she demanded. “Why didn’t I know?”

The pain in her voice cut through me like a blade.

“Your mother thought it was better that way,” I said gently.

“Better for who?” Kathleen shot back. “Better for her, so she could take credit for my tuition payments? Better for Uncle Donald so he could pretend you were poor and needed to sell your house?”

I heard a choking sound, then full-on sobbing—not the delicate sniffles she’d had in middle school over friend drama, but raw, messy crying.

“Grandma, I am so ashamed,” she said. “I am so, so ashamed.”

“Kathleen, you have nothing to be ashamed of,” I said.

“Yes, I do,” she insisted. “I let them convince me you were just this sad old lady who needed to be taken care of. I stopped calling because Mom said you were ‘fragile’ and might get too attached if I talked to you too much. She said it was healthier to give you space to grieve.”

Healthier.

I looked up at the darkening sky, where the first stars were beginning to show.

“So I gave you space,” Kathleen continued. “And meanwhile, you were paying my sorority dues and my textbooks and probably my spring break trip. And I never even thanked you. I never even asked how you were doing without Grandpa. And now they’re telling everyone you’ve had some kind of breakdown and disappeared. But Grandma…”

She took a shaky breath.

“You haven’t had a breakdown, have you?” she said. “You’ve just finally had enough of their—”

“Language, Kathleen,” I said, though I couldn’t help the small smile that touched my mouth.

“Am I wrong?” she asked.

I looked out at the dark water, at the lights of the village beginning to twinkle down the coast.

“No,” I said. “You’re not wrong.”

“Where are you?” she asked. “Really?”

“Spain,” I said.

“Spain?” She sounded stunned. “Like… the country Spain?”

“Yes,” I said. “Your grandfather bought a house here for our retirement. I’m sitting on the terrace right now, looking at the Mediterranean.”

There was a long pause.

“Is it beautiful?” she asked quietly.

“It’s the most beautiful place I’ve ever seen,” I said.

“Grandma, I need to tell you something,” Kathleen said. “I need to apologize.”

“You don’t need to apologize for anything,” I said. “You were told lies by people you trusted. That’s not your fault.”

“But I should have known,” she said. “I should have called you more. Should have asked questions.”

“Kathleen, listen to me,” I said, standing and pacing the terrace, the warm night breeze playing with my hair. “You’re twenty years old. Your job right now is to study and grow and figure out who you want to become. It’s not your job to manage family finances or decode adult manipulations.”

“But I want to do better,” she said. “I want to be better.”

“Then be better,” I said. “Call me because you miss me, not because you need something. Visit me because you enjoy my company, not because you’re obligated. Love me because I’m your grandmother, not because I pay your bills.”

There was another long pause.

“Can I visit you in Spain?” she asked.

The question caught me off guard.

“Kathleen, I don’t know how long I’ll be here,” I said. “I haven’t figured everything out yet.”

“I don’t care,” she said. “I have spring break in three weeks. I can change my plans, cancel that stupid Cancun trip you probably paid for anyway, and come see you instead. I want to meet this ‘grandfather’s dream house.’ I want to sit on that terrace with you and hear about your new life.”

Your new life. The phrase sent a warmth through my chest.

“What would your mother say?” I asked.

“I don’t care what my mother says,” Kathleen said. “Actually, that’s not true—I care. But I’m not going to let what she says control my choices anymore. Grandma, I’m twenty years old and I just realized I don’t really know you at all. I know the version of you they told me about. The grandmother who bakes cookies and sends birthday cards and needs to be ‘handled carefully.’ But that’s not who you are, is it?”

I thought about the woman who had confronted her son in her own hallway, who had calmly dismantled her children’s assumptions, who had boarded a plane to Spain with no return ticket.

“No,” I said. “I’m not that person at all.”

“Good,” Kathleen said fiercely. “I can’t wait to meet the real you.”

After we hung up, I sat in the dark for a long time, listening to the waves and feeling something unfamiliar inside me.

For the first time in months, I was looking forward to tomorrow.

And for the first time in years, I didn’t feel alone.

Three weeks later, I stood just beyond the sliding doors at Málaga airport, watching travelers spill out with their wheeled suitcases and duty-free bags. When Kathleen finally emerged, I barely recognized my granddaughter.

Gone was the polished college girl from Christmas photos—hair perfectly straightened, makeup contoured for Instagram, clothes chosen for likes and comments. This Kathleen wore faded jeans, white sneakers, and a simple white T-shirt. Her dark hair was pulled back in a messy bun, her face free of everything except sunglasses pushed up on her head and a genuine, unselfconscious smile that transformed her.

“Grandma,” she shouted, dropping her backpack and running toward me.

Her hug was nothing like the quick, obligatory squeezes at holiday gatherings. This was desperate and grateful and real, her arms holding on like she was afraid I might vanish.

“Let me look at you,” I said, holding her at arm’s length.

She was thinner than I remembered, but there was a steadiness in her eyes that hadn’t been there before.

“You look amazing,” she said, studying my face. “Like actually amazing. You’re tan and your hair—did you cut it?”

I touched the shorter style Pilar had convinced me to try at the salon in town. “Just a trim,” I said.

“It’s perfect,” Kathleen said. “You look…” She hesitated, searching for a word. “You look like yourself.”

On the drive to Marbella, Kathleen pressed her face to the car window like a child, exclaiming over olive groves, whitewashed villages, and roadside billboards she tried to read out loud with a terrible but enthusiastic accent.

“This is it,” I said as we pulled into the driveway of the Spanish house. “Your grandfather’s dream.”

Kathleen stood in the small garden for a long moment, absorbing the bougainvillea, the lemon trees, the curve of the stone steps up to the terrace where I’d spent so many afternoons reading.

“He knew,” she said finally, her eyes shining. “He knew you’d need this place.”

“I think he did,” I said.

That first evening, we ate on the terrace. Pilar had insisted on preparing a big pan of paella for Kathleen’s arrival, bustling around my kitchen as if she’d always belonged there.

“You must eat,” she told us, setting the steaming pan on the table. “You talk, you laugh, you cry—everything is easier with good food.”

I watched Kathleen respond to Pilar’s warmth with a natural kindness that had sometimes been missing from her interactions with her own parents.

“Tell me about your life here,” Kathleen said later, settling into the chair beside mine as the sun slid toward the horizon. “I want to know everything.”

So I told her—about my morning walks through the village where shopkeepers had learned my name and my preference for fresh bread and strong coffee; about Spanish lessons at a sidewalk café with Miguel, a retired literature professor who lived down the street; about the way the American tourists along the promenade always looked slightly rushed, even when they were carrying beach towels.

And I told her about the notebook I’d bought at the stationery shop, where I’d started writing—not the novel Russell had once encouraged me to dream about, but a memoir. A book about marriage and motherhood and the slow erosion of self that can happen when love becomes service and service hardens into obligation.

“You’re writing a book?” Kathleen said, her eyes widening. “Grandma, that’s incredible. I had no idea you wanted to write.”

“I didn’t know either,” I admitted. “Not really. I never had enough quiet to hear my own thoughts before.”

She was quiet for a moment, watching the sea.

“Mom called me yesterday,” she said finally.

I tensed, but she lifted a hand.

“She tried to convince me not to come,” Kathleen said. “Told me you were having some kind of breakdown and seeing me might make it worse. She said I was being selfish, spending spring break with you instead of ‘the family.’”

“What did you tell her?” I asked.

“I told her maybe it was time for someone in our family to be selfish on your behalf,” Kathleen said, an edge of steel in her voice. “And then I asked her a question she couldn’t answer.”

“What question?” I asked.

“I asked, ‘If Grandma is having a breakdown, why haven’t any of you gone to check on her in person? Why haven’t you called her directly instead of talking about her like she’s a problem to be managed?’”

“What did she say to that?” I asked.

“Nothing,” Kathleen said. “Because the answer would have exposed the truth—that they don’t actually care about your well-being. They care about their access to your resources.”

The bluntness of it should have hurt. Instead, it felt like validation.

“Kathleen, I don’t expect you to choose sides in this,” I said carefully. “Donald and Darlene are your family too.”

“No,” she said firmly. “They chose sides when they decided to use me as a weapon against you. When they let me believe you were poor and fragile while you were paying my bills. When they tried to isolate you from the people who might actually support you.”

She leaned forward, her hands wrapped around her glass.

“They didn’t just lie to you about your finances,” she said. “They lied to me about you.”

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“They convinced me you were this fragile old lady who needed to be protected from too much excitement or emotion,” she said. “They said calling you too often might make you ‘dependent,’ that I should give you space to grieve. But that was never about protecting you, was it? It was about controlling the narrative.”

I stared at her, amazed by her clarity.

“They wanted you isolated,” Kathleen said, “so you’d be desperate enough to accept whatever terms they offered. And they wanted me distant so I wouldn’t see how they were treating you. The worst part is…”

She looked down at her hands.

“…it almost worked,” she whispered. “I almost became the kind of person who could ignore her grandmother’s loneliness because it was convenient.”

“But you didn’t become that person,” I said.

“Only because you forced the truth into the open,” she said. “If you hadn’t left—if you hadn’t made them show their real faces—I might have gone my whole life never knowing who you really are.”

We sat in silence for a few minutes, listening to the sound of the waves and the distant murmur of conversation from a nearby café.

“Are you ever going back?” Kathleen asked suddenly.

“To Ohio?” I said. “I don’t know.”

“But you could stay here,” she said. “Permanently, I mean. Legally.”

“Russell researched it,” I said. “There are residency options, health care plans… everything I’d need.”

“Then I think you should stay,” Kathleen said. “I think you should let Mom and Uncle Donald figure out their own lives without expecting you to fix their mistakes or validate their choices.”

She took a breath.

“And I think,” she added, “that I should transfer to a university here.”

“What?” I stared at her.

“There are American programs in Madrid, Barcelona, even Málaga,” she said. “I could finish my degree in international studies, become fluent in Spanish, learn about a different way of living. Or I could take a gap year. Work with Pilar at her pottery studio. Help you with your book. Figure out who I am when I’m not performing for an audience.”

“Kathleen, that’s a huge decision,” I said.

“So was getting on a plane to Spain alone at sixty-three,” she said. “So was refusing to sell your house. So was cutting your hair and starting a book.”

She turned to face me fully.

“Grandma, for my entire life, I’ve been making decisions based on what other people expected from me,” she said. “What Mom wanted, what my professors wanted, what my sorority sisters thought was appropriate. But sitting here with you, I finally feel like I’m seeing clearly.”

“What do you see?” I asked softly.

“I see that you’re not the fragile old lady they painted,” she said. “You’re probably the strongest person I know. And I see that I don’t want to be the kind of person who abandons someone I love because it’s convenient.”

She squeezed my hand.

“I want to be the kind of person who shows up,” she said. “Who chooses love over comfort. Truth over convenience.”

“That’s a lot to place on a spring break trip,” I said, trying to smile.

“This isn’t just about spring break,” she said. “It’s about the rest of my life.”

The next morning, we sat at the small table in the living room with my laptop open between us. Together we called her university’s advising office. Kathleen spoke with a counselor, explained she wanted to take a temporary leave of absence and complete the semester through independent study and online exams.

Then we walked down the hill to Pilar’s house, where stacks of clay pots dried on wooden racks in her backyard, and asked about the possibility of an apprenticeship.

“It would be my honor,” Pilar said, pulling Kathleen into a flour-and-clay-smudged hug. “A young woman with good hands and a good heart? This is exactly what the studio needs.”

Finally, with the Spanish sun sinking behind us and the sound of distant waves rolling in, Kathleen made one last call—to her mother.

“Mom, it’s Kathleen,” she said, putting the call on speaker at my request. “I’m extending my stay in Spain.”

I could hear Darlene’s voice rising instantly on the other end.

“No, I’m not having a breakdown,” Kathleen said, calm but firm. “I’m having a breakthrough. I understand that you’re angry, but I’m twenty years old, and I get to decide how I spend my time. Actually, Mom, that’s exactly what I’m doing. I’m choosing Grandma because she’s the only person in our family who’s ever treated me like I matter more than what I can provide.”

There was a barrage of words from the other end—accusations, guilt trips, familiar phrases sharpened with fear—but Kathleen waited until there was a pause.

“I love you,” she said. “But I’m not going to be part of hurting Grandma anymore.”

Then she ended the call and turned off her phone.

“Any regrets?” I asked.

“Just one,” she said, smiling with Russell’s quiet determination. “That it took me twenty years to figure out where I belong.”

That evening, we sat on the terrace together, watching the stars emerge over the Mediterranean. Somewhere down the hill, someone was playing an old American rock song on a portable speaker, the guitar chords floating up faintly through the warm night air. For the first time since Russell’s death, the sound of my home country didn’t make my chest ache. It made me feel… whole.

I realized that my story of loss had become something else entirely.

I had lost the illusion of a family that demanded my diminishment. I had lost the role of being a convenient problem to be managed. But I had found the reality of family that celebrated my strength—a granddaughter who chose truth over comfort, my own voice on a page, a house full of light on a Spanish hill.

For the first time in a very long time, I wasn’t just surviving.

I was thriving.